Classes and Objects¶

Python is an object-oriented language - it’s based on the concept of “objects” that contain some fields (variables) and methods (functions). It’s procedures can modify it’s attributes (fields). Everything in Python is an object - whether it’s an integer or a string.

Object is a handy concept to make a representation of something abstract - for example a useful way of storing data in an ordered manner. Reminds you of something?

Yes, a list.

How would you describe a list object? What attributes does it have? When/How is it useful?

Tip

Do you remember the dir(ClassName) command? It lists all the attributes and methods of a required class, such as dir(str).

If you find you need an object that Python does not have, you can create your own. To create an instance of an object, you first need to construct a “template”, that will define what the object will look like and what it’s capable of. The prototype is called a class:

class Player():

This example shows a template of a Player object, which is empy and not very useful right now. To make it more useful, we can add attributes to it - total_count is class

attribute, that keeps count of all the instances of objects of class Player by incrementing a value every time a new Player() object is instantiated.

class Player():

total_count = 0

A class attribute is the same for any instance of class Player, and so you can find out the total number of players through any of them.

Other attributes that could be useful would be instance attributes (different for every instance of an object) name and score.

How will they be defined? And how can we know when a new object is created to increment the total_count?

It is possible to define an __init__() method for your class, which will be used during an instantiation of a new object and which can take in other arguments and

specify an initial state of an object. In this way, when the object player_1 below is instantiated, the player’s initial score will be zero, the name will be as

specified in the argument and total_count will increment by one.

class Player():

total_count = 0

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.score = 0

self.__class__.total_count += 1

Furthermore, we can define methods specifically for our class of objects. For example, class methods update_score() and change_name to update values of name

and score.

class Player():

total_count = 0

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

self.score = 0

self.__class__.total_count += 1

def update_score(self, score):

self.score = score

def change_name(self, name):

self.name = name

Instantiating objects and using methods is rather straightforward:

# Create an instance of an object of class Player

player_1 = Player("teapot418")

player_2 = Player("r00t")

# Change value of score of player_1

player_1.update_score(40)

# Change value of name of player_1

player_2.change_name("bott0m")

Now you might wonder, why does calling methods on player_1 or player_2 work with one argument only, while the method definitions have two arguments?

Surely Python raises an error in this case. As you may have guessed, the instance object - player_1 - is passed as the first argument, and is actually equivalent to

saying Player.update_score(player_1, 40).

Note

The keyword self has no special meaning in Python, it is just a convention. You should use it if only for the reason of making your code more

readable to others or yourself when you come back to it after some time (you can read more on discussion of self in this blogpost by Guido van Rossum - the

father of Python).

Accessing attributes is the same for all objects again: obj.attribute_name. For example, to print the name of a Player object you write:

print(player_1.name)

To create an attribute for a class, you don’t have to declare it in the class definition - they are like local variables in that they spring into existence when they’re

assigned to. In this way, we can create a counter attribute for our player_1 object. What does the following program output then?

player_1.counter = 0

while (player_1.counter < 10):

player_1.counter += 1

print(player_1.counter)

There are many more nuances and useful characteristics of classes that we don’t talk about in this tutorial. If you do want to learn more, look at Python documentation.

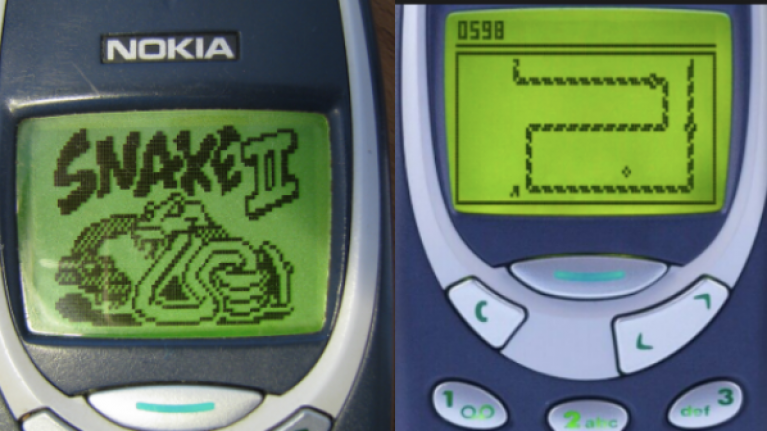

To give you another example of using classes, here is a Snake class that could be used for a micro:bit version of the Snake game (you’ll know if you ever had a Nokia).

class Snake:

def __init__(self):

self.x_position = 0

self.y_position = 0

self.direction = "w"

def move_snake(self, x_position, y_position, direction):

self.x_position = x_position

self.y_position = y_position

self.direction = direction

def show_snake(self):

display.set_pixel(self.x_position, self.y_position, 9)

sleep(600)

display.set_pixel(self.x_position, self.y_position, 0)

# Create an instance of a Snake object

python = Snake()

# Access its position on x axis and print

print(python.x_position)

# Move python to the right

python.move_snake(python.x_position + 1, python.y_position)